今天为大家分享的是“景昱—神经科学专栏”第一百零三期,由上海交通大学医学院附属瑞金医院胡柯嘉带来的:“事件相关STN-DBS影响PD患者冲突处理能力”,内容精彩,欢迎阅读。

基底神经节的一个重要功能是行为动作的选择,当个人面临着多种可能的行动方式的情况,即在反应冲突下,如何进行行为运动的选择显得尤其重要。许多证据表明,皮质-基底神经节环路中的脑区负责对反应冲突(Response Conflict)进行处理,既往研究表明丘脑底核(Subthalamic nucleus,STN)在冲突处理中发挥作用,对应于行为运动的暂停功能,并能导致更慢,更准确的反应。

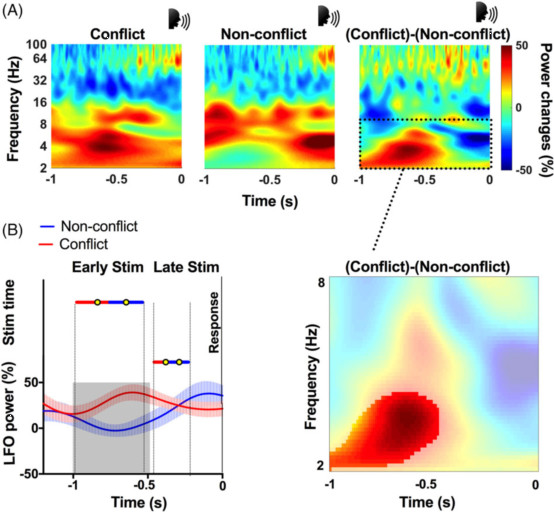

通过脑深部电刺激(Deep Brain Stimulation, DBS)的电极,在基底神经节内记录到来自STN的深部脑电信号局部场电位(Local field potential, LFP),显示了冲突引发低频振荡(low-frequency oscillations, LFO; 2-8Hz)的瞬时增加,而连续性STN的DBS也能在冲突情况下抑制冲动反应,同时功能磁共振成像(fMRI)上也显示出冲突过程中STN的激活。此外,STN对反应抑制的改善DBS也有报道,暗示刺激的效果很可能取决于任务和类型的响应控制。虽然这些研究表明了STN和其所相关的更广泛的基底神经节在抑制冲突处理中的反应,STN和相关运动环路与时间动态的因果关系,特别是LFO所发挥的角色和作用,仍然不清楚。

加拿大多伦多大学Western医院神经内科和Krembil研究所的Robert Chen联合神经外科Andres M. Lozano等研究者部署了一种向STN提供事件相关短列阵DBS刺激的新方法,以测试STN及其环路在冲突相关处理中的作用。该论文发表于2018年8月的《Annals of Neurology》杂志。

(REF: Ghahremani A, Aron AR, Udupa K, Saha U, Reddy D, Hutchison WD, Kalia SK, Hodaie M, Lozano AM, Chen R. Event-related deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus affects conflict processing. Ann Neurol. 2018 Oct;84(4):515-526. doi: 10.1002/ana.25312)

本研究共13例帕金森(Parkinson's Disease,PD)患者,接受了单侧或者双侧STN DBS植入,在第一次手术中,DBS电极导线外置,进行试验,然后IPG装置在第二次手术中被植入。第一次术后1到7天内常规服药后参与语言Stroop实验。研究者选择了经典的言语Stroop任务,其中包括有效比例为1:1的冲突和非冲突试验(参与者命名一个词的颜色,在冲突试验中颜色和书面文字是不同的;非冲突试验中,颜色和书面文字是相同的)。研究者接着在冲突和非冲突试验中刺激状态下4种不同的条件进行分析:

(1)无刺激期;

(2)刺激预反应期(在命令性提示之前);

(3)早期;

(4)晚期(在响应阶段)。

研究者通过刺激PD患者的STN,同时在完成Stroop任务中将短的DBS列阵锁定到试验的特定时期。

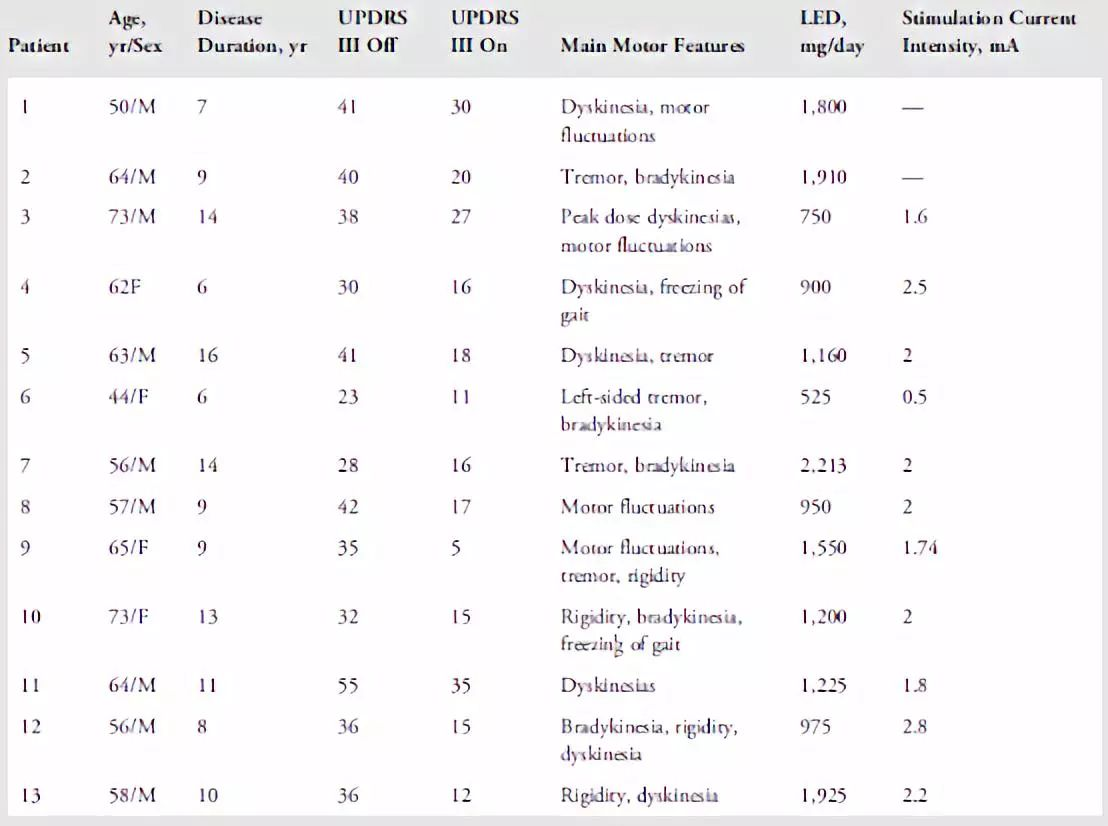

表1. PD患者的临床资料。LED = 左旋多巴等同剂量,计算为100mg标准左旋多巴= 133mg控释左旋多巴或75mg左旋多巴+恩他卡朋(entacapone)或1毫克普拉克索(pramipexole)或5毫克罗匹尼罗(ropinirole)。

为了证实事件相关DBS能增加STN的冲突的事件相关暂停功能,早期或晚期刺激可能会降低错误率并减慢冲突试验中的反应时间(Reaction time,RT)(即,提升“制动”能力)还是说事件相关DBS扰乱了STN和相关运动环路,可能会导致更多错误,会导致更快的冲突试验反应时间?研究者记录了STN的LFP信号,首先测试冲突刺激响应中是否存在既往几项研究报告的早期LFO信号,然后进一步验证在早期或者晚期刺激是否和LFO功率增加相关。

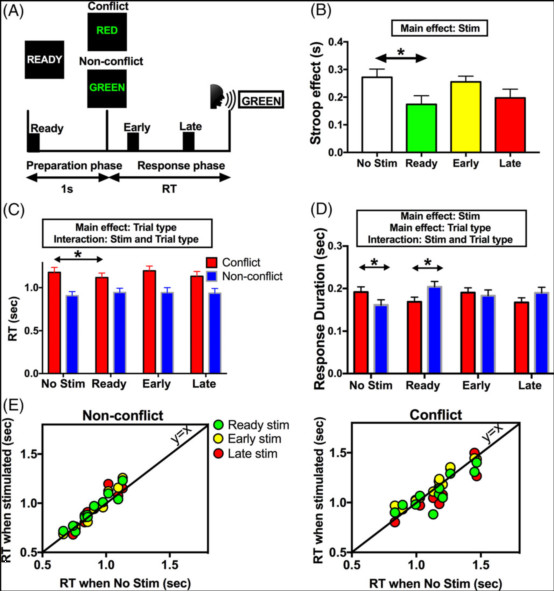

图1:事件相关的深部脑刺激(Stim)影响冲突条件下的发生时间和言语持续时间。(A)Stroop任务。每个试验都以显示1秒的准备cue开始,之后屏幕上会出现一个颜色词。受试者经历冲突试验(单词和单词颜色不匹配)和非冲突试验(两者匹配)。每次试验,一次高频刺激(130Hz,~80毫秒,用黑匣子表示)应用于3个不同的时间点:准备阶段(就绪),以及响应阶段的早期或晚期。(B)Stroop效应在事件相关刺激下显著减少。(C)选择性地在准备阶段(Ready)刺激使得冲突试验期间反应时间减少(RT),而非冲突试验期的RT没有变化。(D)无刺激条件下,冲突实验的语音响应持续时间与的非冲突试验相比更长。然而,在准备阶段与事件相关的刺激下,冲突试验中的响应持续时间变短。(E)个人患者的数据。每个点代表1名患者。非冲突(左)和冲突(右)条件。在冲突实验中RT变快,但在非冲突试验中没有。显示平均值±平均值的标准误差。* p <0.05。

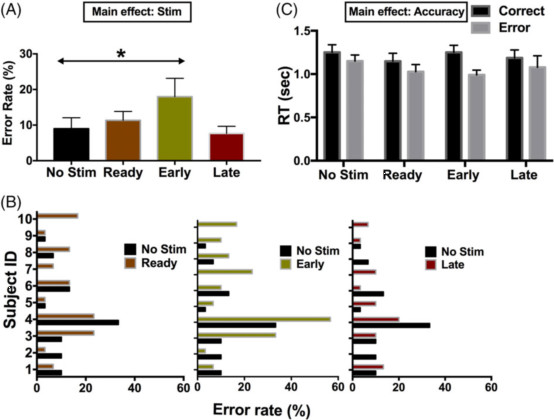

图2:事件相关刺激(Stim)对冲突条件下的错误试验的影响。(A)组平均错误数据:刺激增加了错误率,特别是在响应早期应用。(B)个人数据。(C)错误试验在没有刺激的情况下,明显快于正确的试验。早期刺激似乎使错误试验做的更快,但变化不显着(n = 5)。 显示平均值±平均值的标准误差。 * p <0.05。

研究结果显示,在准备阶段的预反应期进行刺激,相对加快了冲突试验的反应时间。而在响应窗口的早期刺激,也会增加错误率,这一结果对应于在没有刺激的情况下观察到的冲突引起的增加LFO的时间,但与Stroop效应的减少没有直接关系。

图3:冲突期间刺激时机到丘脑底核活动的映射。(A)冲突和非冲突试验显示响应时γ波段功率的响应锁定增加。冲突试验另外显示出增加响应期早期的低频功率(2-8Hz)。虚线框表示要检查的先验感兴趣的带低频振荡(LFO)。插图显示了冲突和非冲突条件之间2到8Hz频段的对比范围。差异显着(p <0.05,红色未掩盖区域)。时间0表示响应开始。(B)在预应答期间相对于显著LFO功率变化得刺激时间(平均值±标准偏差)。和非冲突试验相比,冲突实验在刺激早期但不是晚期LFO功率显著增加。垂直虚线表示刺激时间的范围。灰色阴影区域表示时间从图A中提取的冲突和非冲突试验之间的显著差异。

研究者最后总结道,本研究证实了STN及其相关运动环路参与冲突相关的行为调整,此外,破坏冲突实验准确性的DBS刺激时间与冲突相关低频活动增加的发生一致,表明了皮质-基底神经节系统中尤其是STN的这些慢频振荡特征,标记了冲突相关的认知控制过程。

参考文献:

1.Mink JW. The basal ganglia: focused selection and inhibition of competing motor programs. Prog Neurobiol 1996;50:381–425.

2.Nambu A, Tokuno H, Takada M, et al. Functional significance of the cortico-subthalamo-pallidal “hyperdirect” pathway. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2008;60:543–554.

3.Wiecki TV, Frank MJ. A computational model of inhibitory control in frontal cortex and basal ganglia. Psychol Rev 2013;120:329–355.

4.Fumagalli M, Giannicola G, Rosa M, et al. Conflict-dependent dynamic of subthalamic nucleus oscillations during moral decisions. Soc Neurosci 2011;6:243–256.

5.Cavanagh JF, Wiecki TV, Cohen MX, et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation reverses mediofrontal influence over decision threshold. Nat Neurosci 2011;14:1462–1467.

6.Zavala B, Brittain J-S, Jenkinson N, et al. Subthalamic nucleus local field potential activity during the Eriksen flanker task reveals a novel role for theta phase during conflict monitoring. J Neurosci 2013;33: 14758–14766.

7.Zavala B, Tan H, Little S, et al. Midline frontal cortex low-frequency activity drives subthalamic nucleus oscillations during conflict. J Neurosci 2014;34:7322–7333.

8.Brittain J-S, Watkins KE, Joundi RA, et al. A role for the subthalamic nucleus in response inhibition during conflict. J Neurosci 2012;32: 13396–13401.

9.Keuken MC, Van Maanen L, Bogacz R, et al. The subthalamic nucleus during decision-making with multiple alternatives. Hum Brain Mapp 2015;36:4041–4052.

10.Frank MJ, Samanta J, Moustafa AA, Sherman SJ. Hold your horses: impulsivity, deep brain stimulation, and medication in parkinsonism. Science 2007;318:1309–1312.

11.Ballanger B, Van Eimeren T, Moro E, et al. Stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus and impulsivity: release your horses. Ann Neurol 2009; 66:817–824.

12.Green N, Bogacz R, Huebl J, et al. Reduction of influence of task difficulty on perceptual decision making by STN deep brain stimulation. Curr Biol 2013;23:1681–1684.

13.van den Wildenberg WPM, van Boxtel GJM, van der Molen MW, et al. Stimulation of the subthalamic region facilitates the selection and inhibition of motor responses in Parkinson’s disease. J Cogn Neurosci 2006;18:626–636.

14.Mirabella G, Iaconelli S, Romanelli P, et al. Deep brain stimulation of subthalamic nuclei affects arm response inhibition in Parkinson’s patients. Cereb Cortex 2012;22:1124–1132.

15.Mirabella G, Iaconelli S, Modugno N, et al. Stimulation of subthalamic nuclei restores a near normal planning strategy in Parkinson’s patients. PLoS One 2013;8:e62793.

16.Purzner J, Paradiso GO, Cunic D, et al. Involvement of the basal ganglia and cerebellar motor pathways in the preparation of self-initiated and externally triggered movements in humans. J Neu- rosci 2007;27:6029–6036.

17.Levy R, Hutchison WD, Lozano AM, Dostrovsky JO. Synchronized neuronal discharge in the basal ganglia of parkinsonian patients is limited to oscillatory activity. J Neurosci 2002;22:2855–2861.

18.Aron AR, Poldrack RA. Cortical and subcortical contributions to Stop signal response inhibition: role of the subthalamic nucleus. J Neu- rosci 2006;26:2424–2433.

19.Mirabella G, Fragola M, Giannini G, et al. Inhibitory control is not lateralized in Parkinson’s patients. Neuropsychologia 2017;102: 177–189.

20.Brainard DH. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spat Vis 1997;10:433–436.

21.Hutchison WD, Allan RJ, Opitz H, et al. Neurophysiological identification of the subthalamic nucleus in surgery for Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 1998;44:622–628.

22.Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol 1935;18:643–662.

23.Wessel JR, Conner CR, Aron AR, Tandon N. Chronometric electrical stimulation of right inferior frontal cortex increases motor braking. J Neurosci 2013;33:19611–19619.

24.Neter J, Wasserman W, Kutner MH. Applied linear statistical models: regression, analysis of variance and experimental designs. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin, 1985.

25.Delorme A, Makeig S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J Neurosci Methods 2004;134:9–21.

26.Oostenveld R, Fries P, Maris E, Schoffelen J-M. FieldTrip: open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Comput Intell Neurosci 2011;2011: 156869.

27.Kühn AA, Trottenberg T, Kivi A, et al. The relationship between local field potential and neuronal discharge in the subthalamic nucleus of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol 2005;194:212–220.

28.Ray NJ, Brittain J-S, Holland P, et al. The role of the subthalamic nucleus in response inhibition: evidence from local field potential recordings in the human subthalamic nucleus. Neuroimage 2012;60: 271–278.

29.Maris E, Oostenveld R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. J Neurosci Methods 2007;164:177–190.

30.Ratcliff R, Frank MJ. Reinforcement-based decision making in corti- costriatal circuits: mutual constraints by neurocomputational and diffusion models. Neural Comput 2012;24:1186–1229.

31.Zavala B, Zaghloul K, Brown P. The subthalamic nucleus, oscillations, and conflict. Mov Disord 2015;30:328–338.

32.Aron AR, Herz DM, Brown P, et al. Frontosubthalamic circuits for control of action and cognition. J Neurosci 2016;36:11489–11495.

33.Baunez C, Nieoullon A, Amalric M. In a rat model of parkinsonism, lesions of the subthalamic nucleus reverse increases of reaction time but induce a dramatic premature responding deficit. J Neurosci 1995;15:6531–6541.

34.Baunez C, Robbins TW. Bilateral lesions of the subthalamic nucleus induce multiple deficits in an attentional task in rats. Eur J Neurosci 1997;9:2086–2099.

35.Eagle DM, Baunez C. Is there an inhibitory-response-control system in the rat? Evidence from anatomical and pharmacological studies of behavioral inhibition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010;34:50–72.

36.Jahanshahi M, Ardouin CM, Brown RG, et al. The impact of deep brain stimulation on executive function in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2000;123:1142–1154.

37.Coulthard EJ, Bogacz R, Javed S, et al. Distinct roles of dopamine and subthalamic nucleus in learning and probabilistic decision making. Brain 2012;135:3721–3734.

38.Herz DM, Zavala BA, Bogacz R, Brown P. Neural correlates of decision thresholds in the human subthalamic nucleus. Curr Biol 2016; 26:916–920.

39.Herz DM, Tan H, Brittain JS, et al. Distinct mechanisms mediate speed-accuracy adjustments in cortico-subthalamic networks. Elife 2017;6:1–25.

40.Liebrand M, Pein I, Tzvi E, Krämer UM. Temporal dynamics of proactive and reactive motor inhibition. Front Hum Neurosci 2017;11:204.

41.Duque J, Greenhouse I, Labruna L, Ivry RB. Physiological markers of motor inhibition during human behavior. Trends Neurosci 2017;40: 219–236.

42.Cohen MX. A neural microcircuit for cognitive conflict detection and signaling. Trends Neurosci 2014;37:480–490.

43.Cavanagh JF, Frank MJ. Frontal theta as a mechanism for cognitive control. Trends Cogn Sci 2014;18:414–421.

44.Frank MJ, Gagne C, Nyhus E, et al. fMRI and EEG predictors of dynamic decision parameters during human reinforcement learning. J Neurosci 2015;35:485–494.

45.Little S, Pogosyan A, Neal S, et al. Adaptive deep brain stimulation in advanced Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol 2013;74:449–457.

46.Little S, Beudel M, Zrinzo L, et al. Bilateral adaptive deep brain stimulation is effective in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:717–721.

47.Rodriguez-Oroz MC, López-Azcárate J, Garcia-Garcia D, et al. Involvement of the subthalamic nucleus in impulse control dis- orders associated with Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2011;134(pt 1): 36–49.

48.Herz DM, Little S, Pedrosa DJ, et al. Mechanisms underlying decision-making as revealed by deep-brain stimulation in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Curr Biol 2018;28:1169.e6–1178.e6.

49.Kelley R, Flouty O, Emmons EB, et al. A human prefrontal- subthalamic circuit for cognitive control. Brain 2018;141:205–216.

编者按

本研究提供了在认知控制范式中人类STN事件相关DBS的深部脑电信号,发现从STN记录的LFO时间的变化对应于冲突处理功能的变化,为闭环STN DBS能影响认知功能提供了证据。

同时该研究尚有一些需要进一步探讨的地方:

1. 受限于伦理问题,和所有的颅内记录的局限性类似,样本量较一般认知神经科学实验较少。研究者在PD患者中进行记录,他们的STN活动可能与正常受试者不同。因此,研究者也进行了PD患者在服用多巴胺能药物的状态下的试验,这可能会使STN活动部分正常化。

2. 刺激在STN内的DBS触点不能比较STN背侧与腹侧受刺激的影响,这两者的差异可能需要在进一步实验中进行鉴别。

3. 由于刺激侧的信号饱和,研究者只刺激一侧而不是双侧。之前的一项研究发现(Brittain JS, et al. 2012),在语言Stroop任务中左右STN的功率调节相似,因此双侧刺激可能会产生更大的行为效应。

4. STN刺激(增加冲突试验的错误率)的影响与冲突相关的LFO功率的提升一致,这提出了事件相关DBS可能在冲突中抑制LFO的可能性,未来的研究需要更好地了解为什么随着试验阶段的变化刺激会造成不同的结果。

总的来说,本研究的结果对于更好地理解响应控制中STN及相关环路的动态变化,以及帮助设计事件相关DBS方法的潜在临床意义具有理论相关性。